“The decisions Celeste had to make were very, very difficult,” Clark recalled. “They told her if she didn’t give them permission to remove my arms, I was going to die––and if they did remove my arms, I would likely die. There was a waiting period, then finally she had to step up and say ‘Do it.’ As hard as it was for everyone, thinking I would be waking up without arms and legs, she had to do it.”

“Clark is very strong-minded,” Celeste knew. “I thought that if there were a chance for prosthetics, he would rather live. Now, if the amputations had been higher, with no chance of prosthetics to help him become functional, I think it might have been a different story.”

“The amputations alone could have killed me,” Clark realizes. “—and they had to leave them open. I had a lot of muscle removed from my back, which was also an open wound for about a month and a half. There was a lot of risk with everything they did.”

Weakened by the surgeries, Clark faced myriad additional complications and an uphill battle for survival when he emerged from his coma: he was on kidney dialysis, he had pneumonia, pancreatitis, fevers, a collapsed lung, and more.

He didn’t learn that he was out of the woods until early September, when he was told they would discharge him on September 11 and send him to rehab.

The immensity of the recovery effort that Clark faced is likewise unimaginable. Muscle deteriorates rapidly from disuse; after two and a half months of comatose immobility, he had virtually no muscle.

Clark’s therapy team at Moss Rehab at Elkins Park, which included Alba Seda-Morales, PT, DPT; Drew Lerman, OTR/L; and physiatrist Stanley K. Yoo, MD, began his program with basic muscle relearning.

“Even just sitting up took a month,” he recalls. “Sleeping on my back every night—I couldn’t even move if I had an itch on my face.”

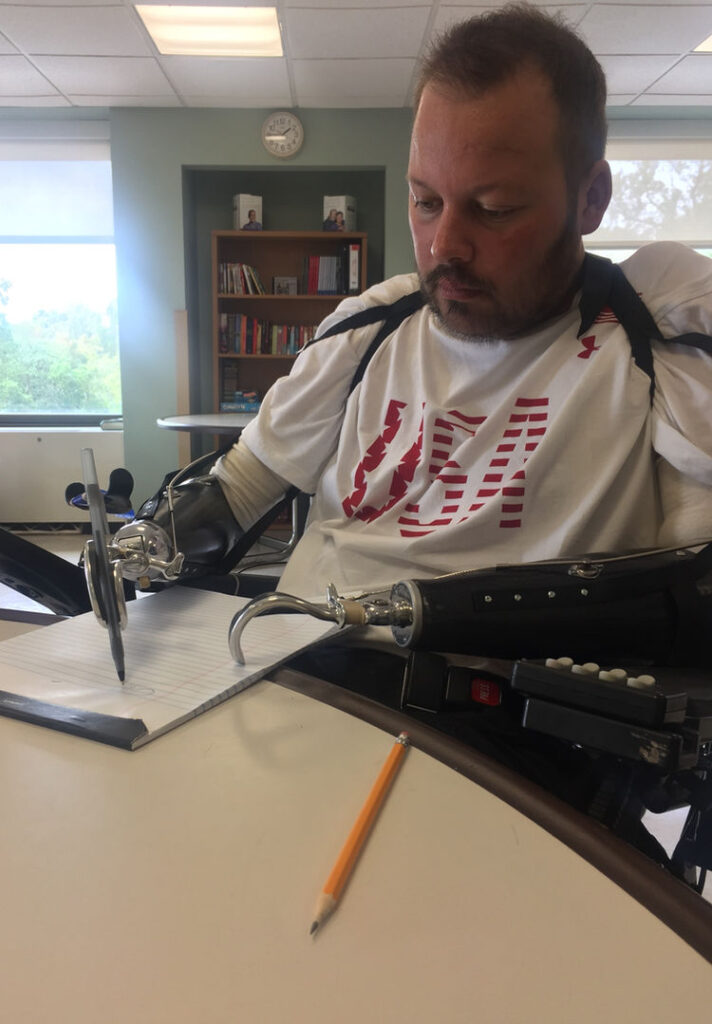

After the first month of core muscle rebuilding, his first prosthetic fittings began. “I got one arm to start with, then very quickly Jack (Jack Lawall, Clark’s prosthetist) made two temporary arms so I could get used to wearing something and building my strength.

Prosthetics are actually pretty heavy, because you’re not only lifting them, you’re lifting them with a smaller part of your leg or arm. The weight is at the end, so it’s heavier than it actually feels for you to lift it with your hand,” he explained.

In another month, the fitting of his leg sockets began. “They start you with very short leg prosthetics because, again, you have to get muscle strength back in order to stand. I couldn’t stand at my original 5’11” height, or I would have just fallen over. With a different center of gravity, you have to relearn everything.

“You start with a straight pole and you walk similar to a penguin, whose knees don’t bend. You have to prove that you can walk before insurance even considers getting knees for you. My amputations are both above-the-knee, which are hard to walk with—and even harder when you have two, which is unusual. I just learned recently that I’m the first person that’s been through the Moss program that’s gotten this far with the knees.”

“According to the therapists and Jack,” Celeste adds, “Clark is about two years ahead of schedule with his rehabilitation progress.”

“That’s a credit to my hard work,” Clark admits, “but also to my family’s hard work, and my therapist’s. And nothing is ever held up by the prosthetics moving forward. If I need another two inches to get to the next stage, Jack is there any time we ask him to be available.”

Although typically Lawall fits patients at his office, or prepares devices there for a hospitalized patient, in this case he adapted his skills to complete everything at the hospital, recognizing that Clark’s nine weeks of in-patient rehab time could not be wasted.

Because Clark’s situation as a quadruple amputee is very unusual, he notes that finding solutions is a team effort: “We work together. That’s the best thing about Moss and Jack; everything is new for us, and sometimes requires different and creative new approaches. I haven’t seen anyone else there who is missing both arms and legs.”

He points out a few of the difficulties most lower-limb amputees don’t face: “If I had arms, I’d be able to put the legs on, and balance by holding onto railings—it’s just a whole different mindset of how you get moving without arms.”

Upper-limb difficulties are unique, as well, when both arms are missing below the elbow: “If you lose one arm in an accident, you have your other hand to help or adjust the prosthetic hand. I have hooks right now, and I have a lot of trouble turning the hook into the position that I need, because I don’t have another hand to manipulate the hook. That’s just one of the many different factors that everyone has been working on.

“Jack tells me to look stuff up—I do, and then we compare notes and we get where we need to go. We’ve gotten a lot done in a short time, really.”

The effort—both mental and physical—for Clark, is huge. According to his therapist, he reports, walking with just one prosthetic leg takes 280% more energy than an able-bodied person uses. Consider that requirement applied to every movement of all four limbs.

“I’m missing a lot of leg muscles—like the calf muscle—that you don’t realize that you use. So I’m basically walking with the upper part of my leg—without knees. If I get to the level of walking up steps, I’ve seen other amputees use their arms to take much of the weight off. I won’t be able to do that, so I’ve got to find a different way or different strength.

“Right now, I’m trying to be independent, but we’re not there yet, because I don’t have the hands to help me get the leg prosthetics on,” he explains.

The worst moment however, was not dealing with pain, or inability to perform a formerly simple task during therapy, said Clark, but upon his arrival home.

“Clark wasn’t there for the baby’s birth,” explains Celeste, “and he was on heavy medication when he first saw her, at two months.”

“So it didn’t process that I had a daughter until I got home, and that was very hard for me, because she didn’t know me,” he remembers. “She would be great with Mom and Grandma, but they would give her to me to hold and she would cry. If I couldn’t pick her up when she was upset, how was this going to work? That was very hard. But now she knows me and comes down and smiles at me every morning.”

His family is all-important—motivating Clark to give the “150%” that enables him to beat the odds and make such astonishing progress in his rehab, according to Lawall. “He has pushed himself to the limits, and that’s why he has done so well. Part of my job as prosthetist is to be aware of a patient’s mental state, and keep them motivated. I didn’t have to do that with Clark, because he did it himself. From Day One, he had it, and it came from his heart. He was an inspiration to me—he was not going to let this keep him down. He wanted to do it for his family.”

Their nine-year-old son Ares was eight at the time Clark fell ill, and Celeste found that to be perhaps the hardest part for her: “—to see him trying to understand the gravity of all of this. His whole summer was spent in the hospital or at the hotel every single day.”

“My wife has done an amazing job,” said Clark, “especially explaining to our son everything that was happening. He’s in a much better place now that I’m home and is just happy that I’m here. He’s very patient and helps me with my prosthetic removal, and putting them on, bringing me water—little things you’d think he wouldn’t like to do—but he enjoys it. We had a very close relationship before, but it’s even closer now.”

Ares even enjoyed the privilege of naming his baby sister. Celeste hoped that Clark would be able to help choose his daughter’s name, once he met her, but the hospital needed to complete the documentation within a month and Clark remained unconscious, so Ares made the choice, and selected “Ava” –“I think because it starts with an ‘A’,” Celeste added with a smile.

Their large extended family has provided both psychological and practical support; Celeste’s mother, a retired nurse, stayed at the hotel with Celeste and Ares to lend a hand when Ava was born; their friends and community chipped in to help, as well.

“We’re very involved with sports—baseball and basketball, which I also coached when Ares played,” said Clark. “They did amazing things for us.”

In mid-May, when Clark and Celeste shared their story, it was less than a year since he had first been hospitalized—and only eight months since he had begun rehabilitation therapy.

“When I came home from rehab November 10, I couldn’t sit up in bed—I still had so much to regain,” he marvels. “I look back at pictures of myself in September and see that I’ve come so far.”

Since then he’s regained skills and learned new ones with his prosthetic hands: “I didn’t paint before, but I gave it a shot for a fundraising event, and it worked out pretty well! I’ve always enjoyed neat handwriting, and surprisingly, when I wrote my signature for the first time, it was very, very similar to what it was before. They say that’s due to muscle memory, and comes from your brain, not whatever you use to write with.”

He goes to therapy three days a week, now—that’s what insurance allows. Occupational therapy helps him learn to use his hands and arms for functions like getting into a car, buckling the seat belt, and other daily tasks. Extensive muscle loss in his infected shoulder left scar tissue that his occupational therapist is also stretching to increase his range of motion.

His physical therapy focuses primarily on strength training for his legs, emphasizing technique and walking to help him progress to adding length (and height!) and getting and using new knees.

“Jack puts every effort into ability for me to get where I want to go, because he knows that I want to push it. Even to use the arms is very difficult for people, so they just don’t do it. They choose not to walk—because it IS hard.

“If I were 60 years old,” Clark speculates, “maybe I’d choose not to go through it all, but I’ve got so much more to live for with my children, and coaching, that I have to push myself, as hard as it is. The great thing Jack has done is allowed me not to be held up waiting for insurance delays.”

Driven by his spirit and determination, Clark’s progress continues on fast-forward:

“We just started the knees this week—no one really knows how long it will take for me to be fully independent with walking, since no one’s done it yet,” he laughs. “I expect to be able to do everything I did before—to walk, run, drive, coach sports. We’ve seen people do it on YouTube videos, but most of them have taken at least five years to get those kind of results. I’ll find out, I guess.”

Lawall expects to complete the final fitting of Clark’s definitive prosthetic sockets for his legs—with their new microprocessor knees—by early June.

“He walked in check sockets for about a month,” Lawall explains, “so I could make adjustments that will ensure that he walks safely and with less energy. How soon will he be an independent ambulator? That’s up to him; I can’t put a time limit on him. He’s done amazing things during the entire journey.”

Currently, Clark uses body-powered prosthetic arms and hands, and moves his shoulder forward to open or close the hooks that serve as hands.

“We’re working with Jack right now to get my oelectric arms, so I won’t need all the straps,” Clark explains. “I’ll be able to trigger muscles in my existing limbs to open and close and rotate the wrist or hand or hook–or whatever specialized attachment I have on.”

Lawall confirmed that he, Dr. Yoo, and Ms. Seda-Morales are working as a team in their interaction with the insurance company to help get Clark the prosthetic coverage he deserves. “We’re working on it right now—and hoping for quick results.”